/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/24014761/2012-10-18-chris-roberts-adds-kickstarter-option-to-star-citizen-star-citizen-and-kickstarter-logos.0.jpg)

The video game industry owes a debt to Kickstarter. Without the crowdfunding platform, many independently created games may have never made it into development. But every success story has its own bumps in the road — although when it comes to the backer community, the tools with which to make it over these bumps aren't always available.

We spoke with a dozen developers who have turned to Kickstarter in the past few years, all with varied experiences. While some felt comfortable managing things themselves, many developers felt the crowdfunding platform's community tools leave something to be desired. It's an important considering for these developers — for creators on Kickstarter, managing a project's community is a top priority, right next to making the game itself.

Not every developer has experienced egregious issues in managing their campaigns. Thomas Beekers, line producer at inXile Entertainment, told Polygon that in the time during and since the studio's two Kickstarter campaigns — for Wasteland 2 and Torment: Tides of Numenara — there have been no issues within the community with disruptive backers. The studio also has had no trouble navigating the community using the tools already available them.

"Our backer community is made up of passionate RPG fans that love and know this genre very well," he said. "They're engaged and critical, but in constructive and supportive ways. We haven't really heard any horror stories to be honest."

Co-founder and executive producer of Harebrained Schemes Mitch Gitelman seconded Beekers' statement, adding that while sometimes angry community members would become aggressive, there was never any serious threat of danger.

"We definitely had unhappy backers when we announced that Shadowrun Returns would contain DRM in the non-backer version but the tone was civil," he said. "The most vocal guy on the subject was very churned up about but it didn't have any sort of fatal attraction vibe. When I responded directly to an email he sent, we had a thoughtful and constructive conversation."

In many cases, developers said backers self-policed the comments, taking it upon themselves to quell any unruly community members or pot-stirrers. Chris "Warcabbit" Hare of Missing Worlds Media, lead developer for City of Heroes spiritual successor City of Titans, said that the project's community has been largely positive about the campaign and the team has "barely" had problems with followers.

"There was one mildly antagonistic fellow who gained the nickname of 'Bieber,' but all he did was explain how the game would be better as, basically, a first-person shopter," Hare explained Polygon. "He would then engage any people who responded to him in a negative way, and attempt to cause a ruckus. Thanks to the maturity and solidarity of our crew, it generally went nowhere."

Hare added that most horror stories he has heard from other developers have largely been about about PayPal, and not so much backers.

Faster Than Light's Justin Ma had a similar experience: a limited few community members were convinced the game would fail and tried to coerce other backers into withdrawing their pledges. Again, as with City of Titans, other backers stepped up to suppress the negativity.

"There were one or two people who were convinced we would fail and they proceeded to try and convince others at any given opportunity online," Ma told us. "Other than that, we really didn't have any problems. The vocal group of our backers were very polite and generally discussed things online like adults; no one harassed as far as I recall; and we had a number of more invested backers who helped us by responding to other people's questions and problems. Some of them are still responding on the forum and our bug reporting interface over a year later."

Eric Chung of Muse Games, developer on Guns of Icarus, said the "surliest of emails" the studio has received were never over-the-top horrible, and usually contact was about gameplay elements backers wanted to see changed. Chung said that no matter how antagonistic backer contact is, it's important developers do not respond on the same level of agitation — rather, killing with kindness is the best route.

"It's just a matter of making of that empathetic connection."

"It's just a matter of making of that empathetic connection and showing them that you're seeing it from their side," Chung told Polygon. "Once we show them that we're also humans on the other end of that [generic] email address, their tone drastically changes. From expletives that'd make Quentin Tarantino blush to language you'd use when talking to your grandmother. It's really the Golden Rule at work here."

Chung reiterated that the openness of Kickstarter allows developers to get in bed with the backers, up close and personal in a way studios working with big publishers rarely can be.

"I think something that also helps is that all of us interact with our players," he said. "Our CEO interacts with players on daily basis from responding to bug/feedback emails to having them on a Skype calls. I involve the community in balancing the game and actively consult them in our forums. Recently, there were some very vocal players who were angry with my changes. It took some massaging but after detailing my intentions and hearing their complaints, we've all come to a middle ground."

Most developers who said they've never had a serious problem with individual members noted instances of vigilante backer activity, community members stepping up to help diffuse unruly individuals and destructive situations. However, a few developers we spoke to ended up in situations that didn't turn out quite so well.

Backers with a less-than-upstanding ulterior motive can camp out in comments, taking it upon themselves to steer conversation in negative directions or spam the developers via the project page. More dangerously, however, is that Kickstarter offers a public platform with which backers can get in touch with these developers, turning the two-way communication channel into an opening for harm. For some, that empathetic connection has no effect or never exists to begin with.

One game developer, who spoke to Polygon under the promise of anonymity, was repeatedly subjected to harassment and libelous statements by one Kickstarter backer, and said they felt utterly powerless to do anything about the situation. The Kickstarter campaign allowed the individual in question a public forum with which to get in touch with the developer — and Kickstarter did not give the developer moderation tools required to remove him from the game's community.

"I was beside myself," the developer said. "What do you do in that situation? Do I contact a lawyer?"

The developer noted that all someone needs to become a backer is one dollar — the minimum pledge amount for all projects — and even then, the dollar is only a promised one. Amazon Payments, Kickstarter's payment method, will only check to see that backers have a credit card that can be charged before approving a donation. If a project is not funded, the donation will not be charged, and backers can always cancel pledges before the campaign ends.

"It ultimately takes what could be a very pleasant experience and turns it into an absolute nightmare."

If you're taking someone's money to fund a project, the developer said, you're also taking their voice as you welcome them into your community — but you should be able to reject a backer and return their money if they are being horrible. If they're behaving badly, they've essentially paid for the privilege to enter a community and be disruptive.

"It leaves you powerless and a target, and ultimately takes what could be a very pleasant experience and turns it into an absolute nightmare," the developer said. "[Kickstarter] provided me with no way to protect myself.

"I understand why they don't want the ability to curate or edit comments, but we need the ability to boot people," the developer added. "The comments serve as a vehicle for us to really see the state of an actual Kickstarter, I want to see that fans that are pissed off or enjoying it, but what I think is not okay is we don't have the ability to say, ‘I don't want your money, I don't want your comments,' especially when things become threatening or libelous. I need the ability to curate my supporters and if someone is being an asshole, we should be able to address it.

"My security comes first. Every single game becomes a community of backers, I have the right to curate my community."

When contacted to contribute to this report, a representative from Kickstarter declined to speak about these issues. He did tell Polygon that project creators do have the ability to cancel a specific backer's pledge by contacting the customer service team, as well as flag comments for their review. A small number of developers we spoke to contacted Kickstarter support for that exact reason — however, most developers said they sought to resolve backer disputes themselves and were comfortable handling situations on their own.

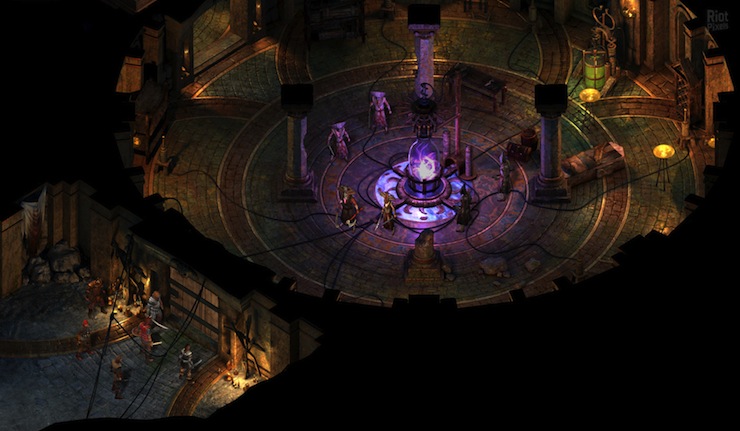

Kickstarter poster child Double Fine has had no issues moderating its community. The studio has launched not one, but two successful campaigns — Broken Age and Massive Chalice — and in both cases, the company felt protected by Kickstarter's tools.

"Kickstarter provides all the barriers needed to make project developers feel secure," Double Fine's Greg Rice told us. "At that point it's just a matter of moderating things and making sure the community stays healthy. For us, that has meant treating our backers like members of the team and being really transparent and honest."

Kickstarter is still in its relative infancy, with Double Fine calling the crowdfunding platform into the spotlight in early 2012. Since then dozens of video game developers have turned to the method to circumnavigate signing up with a publisher. But what many small studios may not acknowledge is that with its audience directly funding a project, they are many more expectations and demands involved in keeping them happy. A publisher can be demanding, but an audience can be fickle, and according to Obsidian Entertainment's Feargus Urquhart, you have to be careful not to promise too much.

"Part of it is, you take the gamer mentality and take more of an investment — part of it is money," he said. "Some have given much more than what they would pay for a game, and they feel – and they should feel — much more of the process. So their expectations of what it's going to be are even more important to them."

But there's a fine line between management and controlling: finding the ideal amount of face time with backers is like balancing on a sliding scale, depending on what's currently happening with a project.

"We've had to manage that, and 'manage' is the wrong term in some ways," Urquhart added. "A lot of it is just having ourselves available to talk to people whenever there's an issue."

Gamers back Kickstarter projects because they want them to succeed and want to help make it happen. Backers can jump into a project with a positive goal, but that passion can sometimes cloud judgment in terms of what is and is not an acceptable way to make themselves heard. Urquhart said Obsidian always strives to keep things positive, taking negativity with a grain of salt and working through the situation to diffuse it. Ignoring the situation or sharing less project updates because of sticky backer situations is not the way to go — in doing so, you risk alienating the rest of your community.

"It's like your 401K — you don't want to not look at it for six months because if you don't look at it for six months you're like oh, it's 20 percent and I'm happy," Urquhart said. "But if you lose one percent, you're really mad and you want to know why you lost it. So we're pushing updates all the time.

"Some backers can take it too far and how you deal with that is hard," he added. "But you know, everyone has an obsessive personalty to an extent."

One individual who worked on a popular Kickstarter, who also requested anonymity, said that the most invested backers live and breathe the campaign, clinging to updates and camping in a project's comments. Crowdfunded projects with more grand scopes tend to have "a lot of hopes and dreams all wrapped up into it," and any sort of threat to not having those dreams realized can manifest a multitude of negative or obsessive behavior.

On the subject of other backers taking it upon themselves to answer other backers' questions and serve as vigilante moderators and representatives for the title, the individual said that this isn't necessary a bad thing, though some may see their constant presence on the project page as a "crazy unhealthy obsession."

"There's a worry all that excitement and energy is going to turn against you."

"I definitely know the type of backer, at least that are super-crazy, sometimes almost scarily, passionate," the individual said. "But not really any who took it too far. To be honest, we pretty much only had good experiences with these types of folks — in the end, anyway. I will say there were times that I definitely worried, 'oh crap, this person is maybe a little too into this, this could go either way.' There's a worry all that excitement and energy is going to turn against you.

"The flipside is, I think you really need these 'crazy' people who are dissecting every tweet and pore over every detail of everything you say," the individual added.

But many of the developers did say there needs to be a way to boot disruptive backers, perhaps a clearer route to do so if the solution is not clearly labeled already. Almost all developers spoken with agreed on one thing: Kickstarter needs a better commenting structure. Ronimo Games's producer Robin Meijer said the current layout of Kickstarter comments makes them difficult to track.

"If you're busy with other stuff, and you're not keeping up on comments, you're a day behind," Meijer said. "Kickstarter stuff starts piling up. That kind of sucks. You can lose track of things — someone can post something and then you're three days behind and you scroll up and they've discussed it more in depth prior to you seeing it. It's hard to make sense of it.

"I'd much rather see a forum structure where someone makes a thread and you can reply in the threat with whatever is relevant there," he added. "As long as you can keep track of it, it's fine. And if you're running a million dollar Kickstarter, it's not sufficient the way they have it right now. If you have 30 to 40 thousand backers, and they're all in the comments section, it's not going to work."

"It's not made to be a message board or IRC chat channel, but those are the things people are using it for," an anonymous project representative said. "So holding a conversation in the Kickstarter comment thread is like screaming across a crowded concert to someone."

On booting backers, developers are more divided. The general consensus is that booting a backer and canceling their pledge is something to be dealt with on a case-by-case basis, and something that could spare studios much grief. But some think that power needs to be directly in the hands of the developers, not Kickstarter's customer representatives.

"It's a good idea for Kickstarter to give the person actually making the project that ability to get rid of people who are only causing problems," one anonymous project representative said. "But Kickstarter is such a wild frontier — think of how much people don't know yet and how developers don't know how people will get involved. It‘s like killing off an invasive species; does that screw up everything somehow? Is there an abuse of that power that I'm not thinking of? Will it piss off other backers? Can projects use it against someone voicing an unpopular opinion? Where does that line get drawn and who decides it?"

Obsidian's Urquhart believes that ultimately the developer running the Kickstarter should be responsible for maintaining a positive atmosphere among the backer community.

"Kickstarter is such a wild frontier."

"Whether it's Kickstarter or Indiegogo, ultimately, if it'm going to people asking for money I'm putting myself out there and I have to deal with it," he said. "I can choose how much of myself is out there and that's on me, and I look at Kickstarter as facilitating this relationship with an audience. But it's ultimately my relationship to maintain.

"There are tools that would make it easier for us to communicate with the community and that would help a little bit... but that wouldn't help with the 1/100th of people who get so engaged that it turns bad," he added. "Are they part of the equation? Yes. Is it a lot of their responsibility? No. I'm the one putting the project up there. I'm getting 95 percent of the funds that come and I choose whether I put my face and name up there or not.

"You can't win the internet," Urquhart said. "We have to remember that. But you can try to correct them respectfully."