Are the rich old men ruining Kickstarter?

The true nature of crowd-funding is being obscured by big names and nostalgia.

At the time of writing, Peter Molyneux's Project Godus, a new god game, has raised £247,044 towards its £450,000 goal on Kickstarter. There are 10 days left to go. Meanwhile, over in Cambridge, Peter's buddy David Braben has raised £699,729 out of £1.25m to make Elite: Dangerous with 24 days left to go. Neither project is guaranteed to be fully funded, but the point is that these grand old men of the British games industry have attracted almost £1 million of support from random people on the internet by promising to return to their roots.

Not that they are blazing a trail, exactly, because the crusty old Americans were at it with this stuff before Molyneux had even handed in his notice at Microsoft. Tim Schafer famously raised over $3m after asking for $400k to make a graphical adventure, and then Brian Fargo wanted $900k to make Wasteland 2 and ended up with $2.9m. They are only the most famous examples. In fact, they're only two of the most famous examples. Basically everyone's at it.

None of this has sat well with me. Maybe these rich old men can't afford to fund the development of their dream projects out of their own pocket - I don't know - but if they can't convince publishers and actual investors to fund them then I think they have to look at themselves and ask why, not look to us. Not to pick on Peter Molyneux, but I can think of plenty of reasons why no publisher or investor would bankroll one of his games without any kind of creative control, which is what £250k's worth of your money is currently promising to do.

Perhaps the worst thing about this situation, however, is that it is confusing people about what Kickstarter actually represents. When I look at the names of these grandee developers, and I think back not just on the games they have produced but also the things they have said about them before release, my first reaction as a potential backer isn't to lick my lips at the concept artwork and drink in the product pitch - it's to consult the Kickstarter Terms of Use to see what recourse I might have if I end up disappointed for one reason or another.

When you approach the documentation with that mentality, it paints a discouraging picture. "Kickstarter does not offer refunds. A Project Creator is not required to grant a Backer's request for a refund unless the Project Creator is unable or unwilling to fulfill the reward." In other words, as long as they ship something, they are covered. What happens if they don't? According to a recent update on accountability, "If the problems are severe enough that the creator can't fulfill their project, creators need to find a resolution. Steps could include offering refunds, detailing exactly how funds were used, and other actions to satisfy backers." Say again? "Detailing exactly how funds were used"?! Brilliant, so I will get an email. Maybe I'll frame it.

"Yes. Kickstarter's Terms of Use require creators to fulfill all rewards of their project or refund any backer whose reward they do not or cannot fulfill," the blog reasserts. "We crafted these terms to create a legal requirement for creators to follow through on their projects, and to give backers a recourse if they don't. We hope that backers will consider using this provision only in cases where they feel that a creator has not made a good faith effort to complete the project and fulfill." In other words, you could always sue them if they do a runner, but if they try their best and happen to fail then probably just forget about it.

Which all sounds enormously depressing. But then there's a reason for that: I'm looking at Kickstarter through the prism of Molyneux and Braben and Schafer and Fargo reaching out of their mansions and rattling their golden cups in my direction. They instantly put me in the mentality of a consumer watching E3 press conferences and online trailers and reading interviews and weighing up a pre-order against the potential fiction of their oft-broken pre-release promises. And this is just wrong. It's not wrong because they are taking advantage of people - which may or may not be the case - but because this is absolutely not what Kickstarter is about.

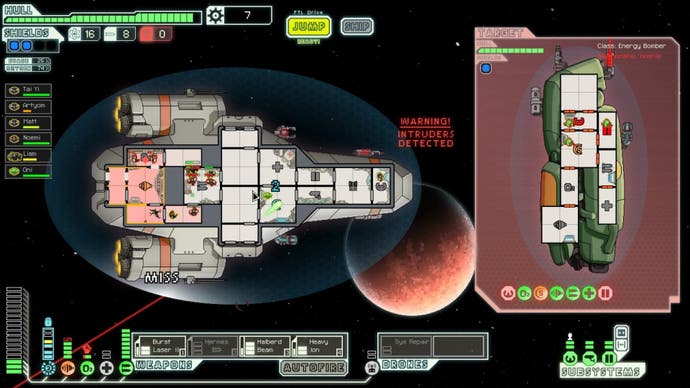

If they weren't there, then nobody would be in any doubt about what Kickstarter represents. Kickstarter is about projects like FTL. FTL: Faster Than Light's creators Subset Games popped up at the start of this year asking for a modest $10,000 to make a spaceship simulation roguelike. They made $200,542. So far so Kickstarter. Then a funny thing happened: they finished it, shipped it, and it's bloody great. As Dan Whitehead put it in our review, "It's one of those games. Games that swallow up your free time like a black hole swallows everything around it. And it's wonderful."

Just this week, Sportsfriends hit its goal of $150,000, albeit only just. It consists of four local multiplayer games - Johann Sebastian Joust, BaraBariBall, Super Pole Riders and Hokra - that exist in prototype form. (I have played BaraBariBall and it's brilliant. Several other Eurogamer writers tell me Joust is also magnificent.) Their creators want to try to prove that there is an audience for this sort of thing, so they sought cash to fund the programming, graphic and sound design expertise that would allow them to bring the games together as a PlayStation 3 title. Sony wasn't convinced enough to fund the project itself, but had agreed to put it on PSN if they succeeded.

These people are not necessarily amateurs, but they are much closer to the French amateur - "lover of" - end of the creative spectrum than the business-minded old men of the gaming world. When asked "Why Kickstarter?", the Sportsfriends quartet wrote: "By self-publishing this compendium, we want to show that the gaming public does indeed care about local multiplayer; that the future of this medium concerns more than just fancy graphics, but also innovative design and replayability; that sometimes, the best games of them all are the simplest." When asked the same question, David Braben said, "Kickstarter is great because as long as we hit the threshold, it commits us to making the game."

Not every Kickstarter goes the same way as FTL and Sportsfriends. A saddening number of big-money projects are behind schedule. But that is the nature of the thing. Kickstarter is about risking your money in support of like-minded creativity, and that's not an exact science.

Since I started writing, Molyneux has picked up another £1308. As for Braben, he's up by £3371. Perhaps all of the people who pledged that money understand that they have not put down a pre-order, and that it might not work out. But I doubt it. The fact that "Kickstarter Is Not A Store" is an official blog post - published as a warning back in September - speaks for itself. "It's hard to know how many people feel like they're shopping at a store when they're backing projects on Kickstarter," the blog begins, "but we want to make sure that it's no one."

Unfortunately, until these big game developers stop using Kickstarter to fund their work, I find it very difficult to believe that it will be no one. I will be happy to play a new god game, a new Elite, a new Double Fine adventure and Wasteland 2, but I would rather they were happening on other terms, and Kickstarter was left to the likes of FTL and Sportsfriends.

-3-31-23-screenshot.png?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)