Roman Through the Multiverse

It has often been said that you can learn a lot about an era by how they portray Rome in its heyday. To the historians of the British Empire, the eternal city was both pomp and melancholy manifest, a promise of what could be accomplished with well-drilled lines of soldiery, but also a lingering reminder that the lights of empire would inevitably wink out. To the fascists of Italy and Germany, it was a city of racial hierarchies, Nordic masters overseeing Mediterranean laborers. For a time Americans regarded it as both an exemplar of civic duty and a suitable antagonist, that great subsumer of individuality and Jesus Christ alike. Later it became the dingy city of corruption and gang rule, populated by kleptocrats stuffing their pockets while sending children to die on foreign soil. I’ll leave it to you to guess which era thought of it in those terms.

The Ragnar Brothers (Gary Dicken, Steve Kendall, and Phil Kendall) aren’t quite striving for that degree of granularity with their latest game, The Romans. Nor do they seem to be evaluating Rome as anything other than a sequence of shifting boundaries. Even so, at some level, The Romans beholds all those contrasting interpretations and seems to query, Why not all of them?

But to make sense of that statement, first we need to talk about parallel universes.

You’ve seen a map of the fullest extent of the Roman Empire before. I won’t belabor the description for you. Suffice to say, it was big, it was diverse, and with so many rivals lurking around every corner, there’s a reason its ascent has stuck in our collective imagination.

More than anything — more, even, than Rome itself — The Romans is about that map. From the spurred boot of Italia cocked in the stirrup of the Mediterranean to the farthest reaches that the historical Romans failed to seize, this is a game about the ways that map expanded, consolidated, and contracted. And if you don’t know anything going in, the first thing you’ll notice upon popping the box open is that it contains four of them.

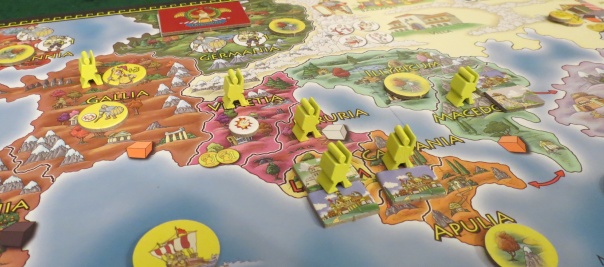

Brace yourself for something unexpected. I wasn’t kidding about that parallel universes thing. Here, the maps are almost identical. Emphasis on the almost. Because while there will never be any significant geographical variances, while Latium will always be Latium and while Gallia never takes a vacation over to Asia, there are a few significant alterations. Resources, for one. Where one map’s Rome produces endless manpower, another turns out iron. Most feature a northern Africa with an impassable midsection; all but one, which permits easy passage between Carthage and Egypt. So it is also along the frontiers. Some feature weak Germanic tribes but stiff-necked Britons, or a far-flung Mesopotamia that’s eager to embrace Roman virtue.

A map of the world as it was known way back when, one for each player, where your own conquests and catastrophes will play out independent of those playing out in parallel realms. But rather than asking everybody to bury their noses in their own affairs, The Romans goes out of its way to entangle everybody in the same pursuits. Turns out, Rome is more than eternal. It’s inter-dimensional.

Every round leads to Rome. In rather straightforward fashion, you begin by placing senators into various locations around the city. There’s a spot for raising legions, for constructing forts and cities and fleets, for collecting taxes from the provinces but increasing local unrest. The forum is for currying political favor, increasing the ranking of your senators and enabling them to access greater benefits; additional free legions, more to spend on construction, and so forth. Over time, the city expands, offering additional senators and new opportunities for the enterprising.

Straightforward, as I said. But what sets it apart is the way it casts you as the antagonist faction of somebody else’s story. And not in the usual way, with everybody hampering everybody else. Rather, your friends’ senators function almost like the faceless rivals of your own city politics. They’re the jealous upstarts, the grudge-holders, the uppity lessers. Everything is gained in that shared space, but deployed into your own world. It’s as though Rome stands at the interstice between dimensions, feeding into a hundred different visions of its own potential. Some will spend more time at home to consolidate power and earn additional coin. Others will dedicate powerful senators to the role of general, leading legions across the map.

Rome as the focal point of imagination and history. The more I say it, the less I think it’s nuts.

Campaigning is more isolated, although the Ragnar Brothers have a few tricks up their sleeves to keep everybody invested. Foremost, everybody shares die rolls. My general heads south to unify Italia, yours hops up to Gallia to secure their precious coinage, our buddy exhausts two fleets at once to reach far-flung Syria, and so-and-so decides to blitz straight for Germania to claim a bonus scoring token. No matter where we are or which barbarian token we’ve flipped, we all tally our strength and then one person rolls two dice, one for us and one for the people we’re hoping to “civilize.” That singular roll is a shared omen, oscines and alites augured by all.

It’s also notably boilerplate, which is where The Romans first settles into a rut from which it never quite recovers. On the offense, there are plenty of mitigative factors to consider. Higher ranking senators make for more proficient generals, although the tradeoff is that they aren’t back home squeezing the populace for taxes or transforming those taxes into points. Similarly, lots of legions can turn aside nearly anything you run into. And that depends on your chosen spot on the era card.

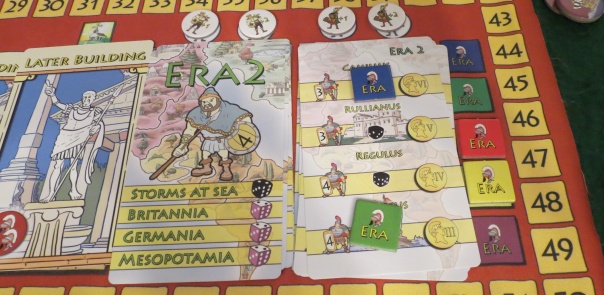

Let’s back up. Twice per round, you flip an era card in Rome. The first time, you’re picking your leader, selecting in order of personal Romes from least to greatest. Your chosen leader provides a few advantages. The occasional free city, fort, or fleet, some cash, and the maximum size of any armies you march out into the world. Pick wisely, because the decision between free infrastructure, a padded treasury, or the breadth of your offensive prowess isn’t one to take lightly.

Despite these factors and tricky decisions, it’s hard to ignore the niggling sensation that you’re investing a lot of effort — and a lot of time, especially as the game’s five eras start to drag into one another — for a sequence of dice rolls. That niggle grows to an itch when you flip the round’s second era card.

In the abstract, the barbarian counterattack is my favorite part of the entire design. After subjecting the map to your idea of a good time, a second era card forces you to choose which horde intends to turn the tables. Like you, these come with soldiers of their own, competent leaders, and sometimes a fleet just in case your control of the seas was too secure. And then the invaders make a beeline toward Rome, conquering their way past everything you claimed, built, and taxed over the past campaign and any previous rounds. If they sack the eternal city, you lose some points for each surviving barbarian — which is no joke, as final scores can hinge upon how much territory was reclaimed by your enemies.

Two thoughts occur to me. First, I absolutely love the tug-of-war dynamic this sparks. Like every other roll in the game, it’s shared between players, often prompting communal cheers or groans as barbarian advances are splintered or flood past your defenses. Also like other rolls, the attacker wins ties. Just as your advance seemed unstoppable a few moments ago, a successful incursion into your territory can feel like the world is coming to its roaring end.

At the same time, these invasions can fill the throat with a measure of bile. On the offense you’re afforded plenty of tools to ensure or neglect your success, but on the back foot there isn’t much you can do to mitigate a tough run of luck. Forts and walls provide a bit of extra defense, but not much. Each province’s garrison is present, but you can’t deploy your home legions in a pinch, or even in defense of the very capital they’re apparently stationed in; for all intents and purposes, they’ve disappeared back into the fold between dimensions. Of course, to some degree your fortunes are shared with your fellow players. But at other times, key provinces will immediately fall because of a stray unrest token, occasionally even one you didn’t have a chance to remove. Fiddling while Rome burns can be a red delight, but when the blaze started because the populace of Elyricum decided they didn’t appreciate that new city you built for them, the tune is a little scratchier.

To be clear, this isn’t a complaint about luck. I wouldn’t go so far as to say that the outcome of the game hinges entirely on a handful of battles. True, territory is crucial for both its taxable resources and the favors the gods bestow for a unified Italia. These favors can prove especially frustrating if you’re the only dictator at the table whose empire keeps losing the toe of their boot and can’t get Jupiter to break wind in your direction, let alone permit a roll for some sweet freebies. But there are plenty of scoring opportunities to chase, in particular if you’re bold enough to seek the triumphs that await those who conquer the map’s farthest regions. Smart play will trounce bad play. Nearly always.

Rather, this is a complaint about how The Romans boasts all these rich, interlocking systems, only to rely on lengthy portions where you have very little say in the proceedings, and then keeps those portions going, and going, and going, until the thrill has gone damp from repetition. The game tries to shake this up in the last two eras by permitting you to convert cities to Christianity, but what does that require? Missionary efforts? Councils? Some sort of investment? Only the latter, and only in the barest form. You have a senator visit your personal citadel and perform conversions rather than earning spare coins. Faster than you can utter a prayer, multiple cities flip from pagan gray to Christian gold. This is a reminder that The Romans isn’t actually all that interested in Rome. Instead of glimpsing a thousand-year city across multiple periods of transformation, there’s no difference between kingdom or republic, empire or church. It’s all about that map, expanding and contracting, over and over. It’s telling that, despite commanding your own pocket universe’s take on Rome, they still manage to blend together.

Despite its weaknesses, I’m fond of The Romans. There’s real care here, an unexpected leveraging of the whole “solo multiplayer” phenomenon, a dedication to providing everybody with an individual sandbox while still forcing the table into moments of friction. Successes on the battlefield are celebrated together; tensions in the senate leave everybody breathing oaths. It’s a rare game that can accomplish even one of those things with much enthusiasm. The Romans somehow pulls off both in the same sitting.

I’ll put it this way. The Romans has certain limitations. Worse, it surrenders to those limitations. But it’s also an ambitious and clever project, a three-hour dice game that doesn’t feel a minute over two and a half, a celebration of Ancient Rome’s breadth that never quite gets past its expansion phase, and an experiment that’s every bit as messy as it is hemmed in. For such eccentricity, I cannot pronounce it either Augustus or Caligula. Elagabalus is more its speed.

(If what I’m doing at Space-Biff! is valuable to you in some way, please consider dropping by my Patreon campaign or Ko-fi.)

A complimentary copy was provided.

Posted on May 12, 2020, in Board Game and tagged Board Games, Ragnar Brothers, The Fruits of Kickstarter, The Romans. Bookmark the permalink. 5 Comments.

“But first (to talk about speedrunning), we need to talk about parallel universes” is one of those phrases that I will remember to my deathbed.

Yep. Same.

It looks like Glory to Rome art. I wonder if that’s cheeky and intentional.

No idea!

Pingback: Review: The Romans:: Roman Through the Multiverse (a Space-Biff! review) – Indie Games Only