Dicebreaker launches news and reviews site to serve thriving tabletop community

Editor-in-chief Matt Jarvis discusses how the games industry can capitalise on the explosive growth of board games

Tabletop and board gaming is currently enjoying a renaissance. Boxes brimming with plastic and card are raising millions of dollars on Kickstarter, while Dungeons & Dragons is suddenly one of the biggest hobbies on the planet.

What's so interesting about the rise of board gaming is how it plays by different rules to the games industry, and yet the two sectors can benefit from collaboration. Dungeons & Dragons is back in vogue, and with it comes the return of games like classic franchises like Baldur's Gate. Meanwhile, game companies are recognising the potential of board game adaptations -- that's not just themed Monopoly or lazy brand cash-ins either, but entirely new games inspired and built around an IP like Doom, X-COM, or the recently announced Divinity: Original Sin.

Launching today, our new sister site Dicebreaker will be covering this rapidly-growing industry, its games, and the people who make them.

"Our tagline is literally, 'board games for everyone'," says editor-in-chief Matt Jarvis. "We have the knowledge and we have the insight and professional tact to cover things in a way that people who are already into board games will hopefully come to us for... You might have played Settlers of Catan, you might have played Monopoly; you can come and read an article and still understand and still feel part of that community and that hobby."

Previously editor-in-chief of Tabletop Gaming, and a journalist for games B2B publication MCV before that, Jarvis is well-placed to recognise the cross pollination of these these two industries. In recent years, canny developers and publishers have been capitalising on the explosive growth of board games and the sector's highly-engaged audience. Titles like Bloodborne and Dark Souls raised over $4 million each on Kickstarter for board game adaptations, while the Resident Evil 2 board game pulled in over £800,000 through the platform.

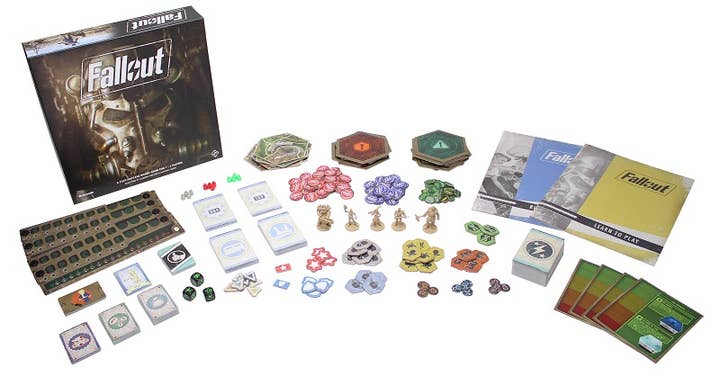

With the growth of tabletop comes an opportunity for video games. Outside of Kickstarter, we've seen successful board game and tabletop RPG adaptations of franchises like The Witcher and Fallout. Just last month, independent UK studio Rebellion Developments announced it was launching its own board game division, while French publisher Asmodee Digital has flipped the script to develop a video game adaptation of the wildly successful big-box dungeon crawler Gloomhaven.

"It's been interesting seeing what they do with adaptation of mechanics, because obviously video games are such a particular style -- you pick up a controller and generally you know what you're doing," says Jarvis. "An FPS is an FPS. But with board games, you can have so many different mechanics, with the same theme. There's the Bloodborne board game, but there's also the Bloodborne card game, and they're so vastly different but based on the same concept. It's fascinating seeing designers pick up mechanics and try to take them in their own direction. It's almost like you get the sense of, 'Okay, this is what they see as the most important facet of this video game'."

Of course, with any good opportunity comes wasted potential. The Fallout board game from Fantasy Flight is a good example of this, Jarvis says. While it created a robust and dynamic story engine that many players will recognise as a core part of the Fallout experience, it played too heavily into aspects of board gaming that don't necessarily translate well to a property like Fallout, like competitive scoring of victory points to end the game. It can also go too far in the other direction.

"I think sometimes there is a risk of them trying to be overly faithful," says Jarvis. "With video games, the code is running the rules behind the scenes. Whereas for board games, it's the people who have to do everything. So if you to just recreate a video game straight up, people are having to move cards around, pieces around, the rule book is 100 pages long... The best video game [adaptations] are the ones that stick to the spirit of the game, but also manage to do something interesting and different."

It's not just massive global brands that can find success moving onto the board game space either. Binding of Isaac developer Edmund McMillen secured $2.6 million for a card game adaptation through Kickstarter, and Nerial raised just over £100,000 for a party game adaptation of its narrative mobile title Reigns. While there are concerns that the "bubble will burst," especially regarding Kickstarter, the industry keeps going from strength to strength, and developers can capitalise on their existing audience through adaptations.

"They just want to be in that universe more and it gives them something different. It almost serves the purpose of merchandise as well, because it's a physical object they can display. That's where you see a lot of the success, is when they really tap into universe of it. It doesn't have to be the game again. You can give people a different window, and let them see more.

"It doesn't have to be the game again. You can give people a different window, and let them see more"

"The tabletop RPG of The Witcher, it is The Witcher, but it's not The Witcher 3. It's letting them see more. It's a lore book, it's an art book, it's all of these things that people might buy separately bonded to one, and also they are able to play it with friends. So it just gives people a way of experiencing the games they are interested in, more so."

Board and tabletop games present another great opportunity for developers and publishers when it comes to diversity of mechanic and theme. While it's possible to break tabletop gaming down into a few genres, there is incredible variety within those spaces. This opens things up for gaming companies looking to grow into a multimedia brand.

"One of the biggest games this year was Wingspan, which was literally about birds, and it kind of came out of nowhere," says Jarvis. "It's by a first-time designer, her first published board game, and it was published in the New York Times and it's picked up endless awards. Just suddenly it was there and it was the biggest thing in the world. There's loveliness to the board game industry in that it's completely unpredictable half the time, because a game about birds can be the biggest thing in the industry suddenly."

Similar to the indie game space, tabletop design teams are small, and often driven by the creative vision of one individual. Wingspan designer Elizabeth Hargrave is an ornithologist who wanted to make a game about birds; as development costs are lower, there's more scope for strange ideas and experimentation. For game companies, this means successful brands can be adapted into all sorts of weird and wonderful tabletop experiences, making it easier to find an appropriate audience or carve out a niche.

"The best video game [adaptations] are the ones that stick to the spirit of the game, but also manage to do something interesting and different"

"There are fewer hoops to jump through, there isn't a large team of developers working for years and years and years as you have in video games, with the guidance of a very large publisher that's looking at millions of dollars rather than thousands," says Jarvis. "There's maybe more room for those ideas to make it out and find an audience as well."

Jarvis says there is something about the familiarity of board games which makes them accessible. Everyone has played Monopoly, which while a far cry from the sort of games Dicebreaker will be covering, demonstrates there is a shared language in a way that video games often struggle with. Additionally, with the rise of live-service games and the move away from couch multiplayer, board games are filling in those social gaps.

"In general you don't see as many local multiplayer games. You've got Jackbox and a few games here and there, but generally I think for a particular generation who grew up huddled around an N64 playing Mario Kart, there aren't nearly as many games now and so they are now turning to board games in a lot of ways, to give that kind of party experience. Where you would previously play Mario Kart at a party, you might play Cards Against Humanity... or another party game that's much better.

"So I think that's part of it as well. You've got the physical renaissance, the likes of vinyl coming back into fashion because there are privacy concerns around digital stuff, and people feel like they don't really own the things that they buy -- like whether your whole Steam library will vanish. Whereas a board game you can hold in your hands, you know you own it."

This is where Dicebreaker comes in, Jarvis says. There are countless board games out there, a growing audience that gets larger by the day -- thanks in part to big-name brands entering the space -- but limited resources for the audience.

"At the moment the industry doesn't have as much discoverability as it should have. How many people play games? People play Monopoly but they have never heard of half of the other stuff. That's why when people discover [Settlers of] Catan it's like, 'Wow, this game is amazing, even though it came out 25 or 30 years ago.' But they are only just discovering because it's taken that long to filter down to them... And that's where something like Dicebreaker comes in: it doesn't matter if you're already playing board games, we've got something for you. If you've only ever played Monopoly, we've got something for you. And we'll be playing stuff better than Monopoly."

Disclosure: Dicebreaker is owned and operated by GamesIndustry.biz parent company Gamer Network.