Peter Molyneux and his team at indie developer 22Cans have not been having a good week. It started on Monday, when Rock Paper Shotgun published a report highlighting the fact that Kickstarter backers are still waiting for a promised PC version of god-game Godus, nearly two years after the game exceeded £500,000 in funding. Though the Kickstarter pitch promised development would take "seven to nine months," backers are still stuck with a buggy "early access" PC version that is missing key features like combat, a "hubworld," and multiplayer support (a mobile version of Godus launched last year with the help of a third-party publisher).

Despite this, recent reports suggest that 22Cans was planning to shrink the Godus development team in favor of a newly announced mobile project, The Trial. As one frustrated new 22Cans developer put it on the game's message boards, "to be brutally candid and realistic I simply can't see us delivering all the features promised on the Kickstarter page, a lot of the multiplayer stuff is looking seriously shaky right now especially the persistent stuff like hubworld." Molyneux and his team took to YouTube to reassure backers, and the public at large, of the game's continued development.

The bad news continued on Wednesday, when Eurogamer published a fascinating piece about Bryan Henderson, who had won the opportunity to share in the revenues from Godus in exchange for serving as the game's first "God of Gods." After some initial enthusiasm on both sides, contact between Henderson and 22Cans fell away, and the promised revenue share and "God of Gods" functionality are still pending more than 18 months later. In response to Eurogamer's article, Molyneux said he "totally and absolutely and categorically apologize[s]" to Henderson for not living up to his promises.

Molyneux's week culminated today in an extremely contentious hour-plus interview with Rock Paper Shotgun's John Walker, in which the journalist leads off with the extremely blunt question of "Do you think that you’re a pathological liar?" Things only go downhill from there, as Molyneux scrambles and stumbles over timelines and facts, alternating between apologies and defenses, while Walker vacillates between "tough but fair" and "tough but unfair."

The full interview is well worth your time, if only to see Molyneux accusing Walker of trying to hound him out of the industry and promising to cut himself off from the press completely in the future. That's a bold claim for a developer with a well-deserved reputation for grandiose game design promises that fail to pan out in the end (a reputation that has led to its own hilarious Twitter parody account). For what it's worth, the mind behind classics like Populous, Black and White, and Syndicate told Ars in 2013 that he thought "Godus is going to be the best game I've ever worked on."

In his Rock Paper Shotgun interview, though, Molyneux insists continually that there's a difference between this kind of naive early optimism regarding a game's promise and flat-out knowingly lying in order to secure funding. He also insists that Godus' many unmet promises simply haven't been met yet and will be in the fullness of time (with a few exceptions like a dropped Linux build).

The Kickstarter problem

Whether Molyneux is a liar or merely a starry-eyed dreamer will continue to be a matter of some debate. But the most important point about the whole Godus debacle that I've seen so far comes from an interview Molyneux gave to TechRadar in December. There, Molyneux blamed much of Godus' troubled development, and even the lofty promises he made regarding the game, on Kickstarter itself.

"There’s this overwhelming urge to over-promise because it’s such a harsh rule: if you’re one penny short of your target then you don’t get it. And of course in this instance, the behavior is incredibly destructive, which is 'Christ, we’ve only got 10 days to go and we’ve got to make £100,000, for fuck’s sake, let's just say anything.' So I’m not sure I would do that again."

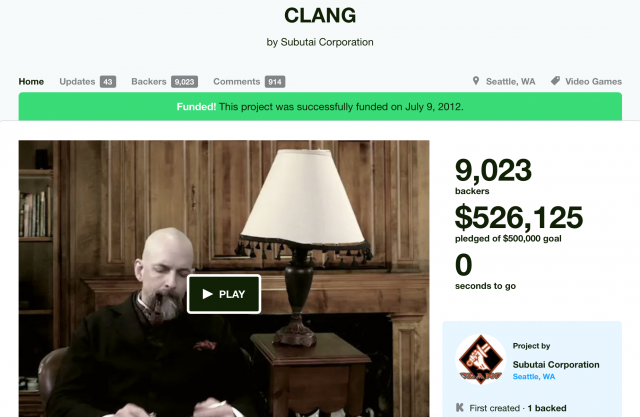

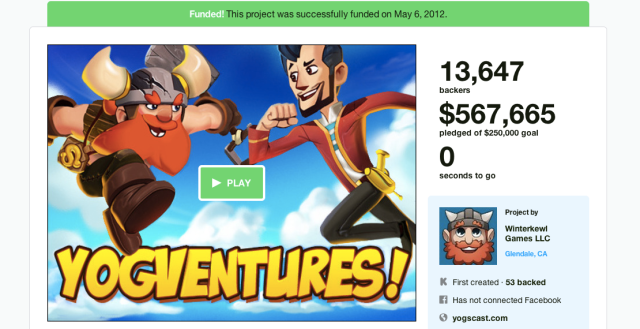

Whatever you think of Molyneux and his history of lofty game design ideas, it's hard to argue that Kickstarter doesn't encourage this kind of thing. In the nearly three years since Double Fine made Kickstarter a serious place to seek game funding, the site has gained a reputation for lofty promises that often don't pan out the way the backers or the developers expected.Examples of this phenomenon are easy to come by in the gaming realm. Multiplayer horror game Haunts was one of the first big Kickstarter game failures, with two developers abandoning the project in favor of full-time jobs after raising $42,500. Swordfighting simulation Clang rode support from fantasy author Neal Stephenson to $526,000 in funding before running out of money and failing to deliver anything past an alpha version. YouTube sensation Yogscast raised $567,000 for a themed adventure game before officially canceling the project in July (backers got a different game in penance). I could go on.

Kickstarter gaming projects that don't fail outright often fail to deliver on promised features or timelines. Many "early release" backers of the Ouya didn't receive their Android-based console until after it was already on store shelves, forcing the company to provide them with store credit in apology. When Kickstarter darling Elite: Dangerous removed a promised offline mode from the final release, some backers demanded refunds. Even Double Fine's Broken Age, which kicked off the Kickstarter gaming boom, ended up significantly delayed and over budget by the time its first episode came out last year.

This doesn't mean that every Kickstarter project is fated to miss its goals; there are plenty of examples of successful projects that delivered quality games to their backers on time. But there may be fewer of those than you think. Overall, one analysis last year found only 37 percent of Kickstarter gaming projects had fully delivered on their promises to backers at least a year after their initial funding. Another 8 percent rated as "partial delivery," while only five percent had been officially canceled or were on hiatus. Much of the remainder had simply gone dark, taking the money and running, as it were.

A mismatch between rewards and penalties

This isn't a problem that's exclusive to crowdfunded gaming, of course. Games built under the traditional developer/publisher model get delayed and canceled all the time, sometimes very close to their promised release. The difference in these cases is that the publisher is the one assuming the risk inherent in these delays and cancellations. With Kickstarter, it's the potential players themselves that assume the risk, even though many users seem to treat the service merely as a way to pre-order interesting games.

The publisher model also serves to hide a lot of messy development realities from the end user. Big-name developers will often work on a project for months before they're ready to announce its existence or show an early conference build to the press. By that point, the developer usually (but not always) has a good idea of the game's structure and what features are possible in what sort of general timeline. Even in that case, though, they might be vague or reticent about making too many concrete promises regarding eventual features.

With Kickstarter, developers are often expected to make detailed promises about a game's features, budget, and development timeline before that development has even started or when it is barely off the ground. The culture of the service encourages developers to be as transparent as possible about the entire process, making any modification or delay an extremely public failure. That's in contrast to traditional development, where unannounced features may be attempted and canceled quietly behind closed doors. The fact that Kickstarter developers are often small independent outfits with less experience with the rigors of development doesn't make these problems any better.

And this gets back to Molyneux's quote about the "let's just say anything" nature of Kickstarter projects. When the site doesn't give a penny to projects that don't meet their minimum stated goal, developers are naturally going to lowball their budgets (consciously or unconsciously) to maximize their chances of getting any funds at all. Faced with a skeptical public and competition from dozens of other projects (many with established developers behind them), Kickstarter projects are also going to be as optimistic as possible regarding promised features in order to attract those backers. Being sober and realistic, in this case, is bad for business.

While Kickstarter's policies technically treat funded projects as a legal contract to deliver on promised pledge rewards, in practice there's almost always no penalty for failing to meet the goals laid out on a Kickstarter page (short of a class-action lawsuit from the backers). The only protection backers really have is the fact that a developer's reputation will be ruined if they fail to deliver—a fact that's little protection when it comes to newly formed studios full of no-name developers.

When Kickstarter's structure offers every benefit to overpromising and little-to-no penalty for not delivering, it's no wonder that those behaviors are so common to projects on the site. You don't need to be a serial, pie-in-the-sky over-promiser like Peter Molyneux for your crowdfunding dreams to outpace your funding and timing realities. When it comes to Kickstarter, everyone is Peter Molyneux, and the backers are the ones enabling their often unachievable dreams.

reader comments

160